|

I first became interested in non-communicable diseases and their intersection with poverty when I was a CGPH fellow during my master’s. I spent 3 months in Rio de Janeiro studying diabetes and hypertension. I was very interested in why, with free and available medications, and an active community health worker system the majority of patients still didn’t have their diseases under control.

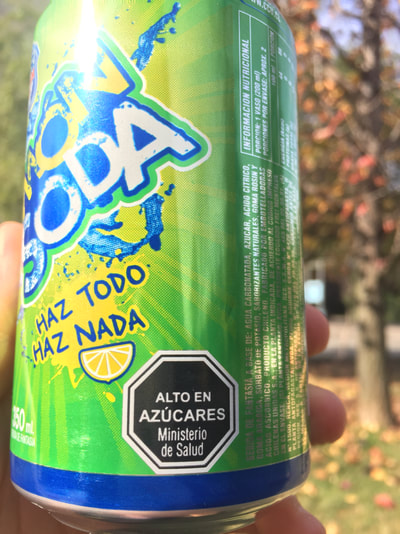

Now, as a health policy PhD student I am especially interested in non-communicable disease policy. This summer (actually, winter!) I spent several months in Santiago, Chile researching reasons for continued non-control of non-communicable diseases like hypertension and diabetes. About three quarters of the Chilean population uses the public healthcare system, FONASA, funded primarily by a 7% tax on wages (for those above a certain income threshold. Not only does FONASA provide medications for non-communicable diseases totally free to its users, the system is also home to several innovative health policies: in 2016 the Nutritional Composition of Food and Food Advertising act was passed, requiring among other things the labelling of all processed foods that are high in sodium, sugars, saturated fats, and/or calories (per 100g), and restrictions on advertising these foods to children. See below for the labels on a jar of Nutella and a can of soda. The Food Act was the government’s responses to rapidly worsening health statistics: Chileans have the highest per capita soft drink consumption in the world, and 60% of the population is overweight or obese. Whether they cause substitution away from these foods is yet to be seen – as far as I know several academics in addition to the ministry of health are currently evaluating the policy. A second innovative health policy – and one I worked on evaluating this summer while in Santiago – is the PSCV appointment reminder program. This program, which was phased in to primary care clinics over the past three years, signs up patients with non-communicable diseases for text message reminders. Patients receive a reminder before their scheduled appointment. They can respond to confirm the appointment, or reply that they wish to reschedule. The text message also serves as a reminder to take their medications. Not only does this text message serve as a nudge to keep NCD patients in care, it also allows the primary care center to reallocate appointment slots if the patient texts back that they wish to reschedule the appointment. Our hypothesis is that this program will not only improve health, but cause positive spillovers to patients not directly enrolled in the program who are now able to get same-day primary care appointments. My summer (winter) spent in Santiago working in collaboration with researchers at the Universidad Catolia de Chile was an enriching experience, and left me with more questions than I began – good news for a graduate student! I will be continuing to work with the mentors and peers I met this summer, and am grateful for the continued support from the Center for Global Public Health.

14 Comments

Traveling almost half way across the globe to conduct my internship in Vietnam this summer has been an incredible journey. Thanks to support from the CGPH, I have had a chance to revisit my homeland to work with the Wildlife Conservation Society Vietnam on the Emerging Pandemics Threat Program initiated by USAID through a project called PREDICT-2. In the second phase of now a 9-year long project, WCS continues collaborating closely with the government and local partners to conduct biological and behavioral surveillance for better understanding of the risk of spillover of viruses of potential public health significance at the human-wildlife interface. The interdisciplinary approach of the project has introduced me to new regions throughout the country and a network of researchers and local communities working together to prevent zoonotic diseases in humans and animals. Our office is located in the capital Hanoi in the North of Vietnam. I spent about one third of my time here in the office, and for the rest I went on field trips collecting samples, assisting with qualitative research, and ran diagnostic tests in PREDICT partner laboratory at the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology (NIHE). My very first sampling trip was done at various locations in Dong Thap Province that stretches along the Mekong delta in southern Vietnam. Near the receiving end of the generous river system is a plethora of tropical fruits, vegetables, and endless green rice fields in the summer intertwined with a number of wildlife farms and live animal markets. Amid local markets selling a variety of terrestrial and aquatic animals and meat, at one point our team, which was led by local authorities, looked for the stands of field rats or “chuột đồng”. This taxa (rodents), which is one of the three primary taxa of our focus besides bats and non-human primates, is considered a specialty by the local people and has such a high demand that they are sometimes imported from neighboring countries, like Cambodia, for consumption. Cages carrying rats can be spotted from a near distance around the meat market, or people can find them at other private vendors in this region. Another interesting field site I visited was at two bat guano farms. These are artificial structure built with high stalls covered by coconut leaves to attract bats on top and gather their excrement on the basement for fertilizer. While the risk of disease spillover is still to be elucidated at this human-wildlife interface, these various field sites are an integral part of the local people’s daily life, illustrating various ways of interactions, directly or indirectly, between humans and wild animals, and apparently they represent an important node in the One Health triad interconnecting also with human and environmental health. The mission of the surveillance project is not only trying to protect human health by proactively detecting virus at its source, but also implementing wildlife protection strategies for endangered species. I was also fortunate to be able to participate, during my second field trip, in a health check for pangolins with Save Vietnam's Wildlife team in Cuc Phuong National Park. These pangolins were confiscated by the authorities from wildlife trafficking network and were undergoing health check before they were released back to their natural habitats in July. Working with this critical species was a rare opportunity, and I have been extremely grateful to be on the sites with dedicated team of veterinarians and staff working at the intersection of human and animal health to protect the health for all. Besides tremendous support from the CGPH, I would like to thank Dr. Peter Dailey for guidance with the project proposal and Dr. Amanda Fine as well as WCS Vietnam staff for welcoming me to the team and making these experiences possible. Huong Nguyen Photo credit: WCS Vietnam Health Team |

ABOUT: Archives

September 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed